Been working on the prologue for Tinselfly. Here’s what it looks like right now:

The idea is, it’s the sort of world-introducing stuff you might get in a start-of-game text crawl or cutscene, but playable (if only in a walking-simulator sort of ‘playable’ way).

Filling out details in each of these scenes has been a bit of a slog lately. I’m having the hardest time figuring out how to move this forward, and I feel like I don’t know how to evaluate the worth of what I’m making.

I think I’ve figured out why that is: I haven’t defined my goals properly, so progress towards my stated goals doesn’t really feel like progress. If you asked me a few days ago, I’d have said the goals of this opening were:

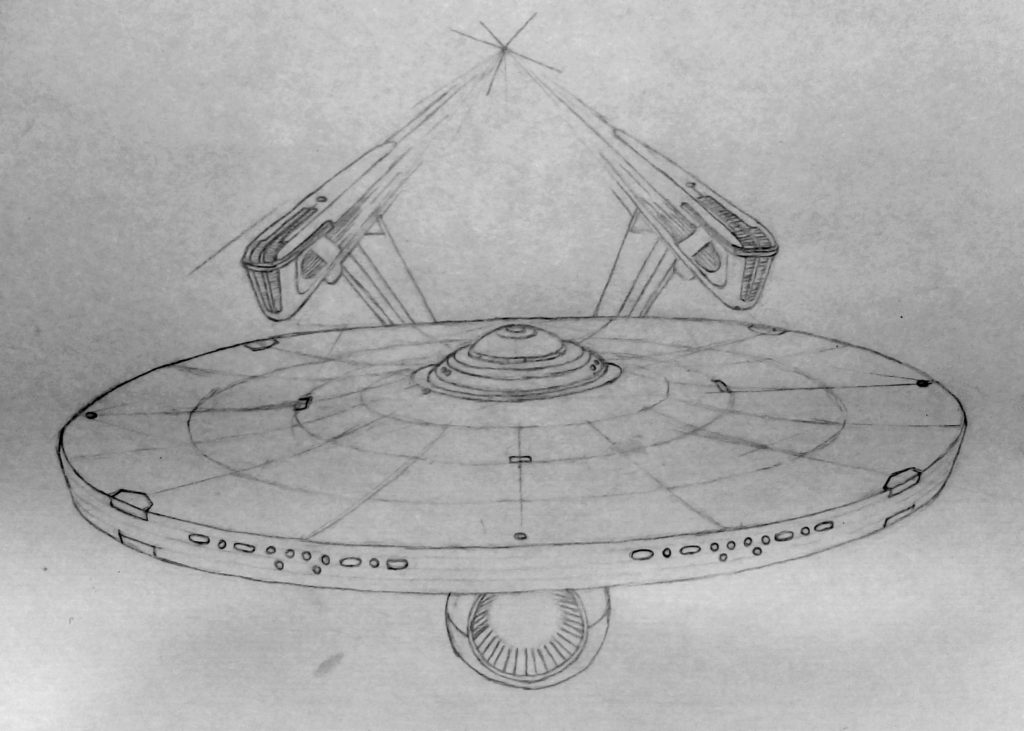

To present a quick, whirlwind history of the Iris, a ship which features in the game’s story;

To make it abundantly clear to the player that the story of Tinselfly will be presented in a unique, stylized, theatrical way, which includes things like playable crossfades and montage sequences.

These statements are true, but as a stated goals, they’re not really my goals for the opening. They also don’t help me come up with specific environmental details, player actions, dialogue or voiceover text. The goals as stated above feel more well suited to a tech demo than a story opening, and Tinselfly does indeed feel like a tech demo right now.

My real goals are more like this:

To quickly and memorably introduce the player to the Iris, showing different people’s relationship to it during different periods of its life.

To make the player feel a sense of wonder and joy at the Iris’ construction and service, and a sense of loss at its destruction.

The history is still there. The bits about a stylish presentation have been removed; that’s the strategy for being memorable, not the goal itself.

Most importantly, these goals are about people and story. If making decisions with the old goals in mind were producing something tech demo-like, then my hope is that making decisions with the new goals in mind will help me add details that make this feel like a story opening — which, of course, is the whole point here.

* * *

So what are the next steps here?

Generally, I think ‘quick and memorable’ are already taken care of; the montage format is pretty unique to games, and the whole sequence, even with more details, shouldn’t take long for the player to complete.

So I need to concentrate on:

- Showing how people in each of the scenes relate to the Iris, rather than just showing what they’re doing.

- Then, taking the Iris away from the people — and the player — that they might feel a sense of loss.

Specifically, here are some ideas:

- Construction scene. I’m not sure a lot needs to change here, just more details, more workers in the background, some chatter about the work.

- Launch party. Needs more people, excitedly watching the ship launch. A friend brought this up a while ago — the ship is very static, and may not even register as a ship since it’s such an odd design. It needs to move, and the launch needs to be mesmerizing. Extras need to stare in slack-jawed wonder at the ship, and the player has to believe they feel awestruck by this.

- Mushrooms. Once the ship is high in the air, fade to it landing on the mushroom world. Excited travelers exit the ship immediately after it lands. And the person flying off into the distance?… I like the transition from that to them flying through the oppressively lonely hangar; maybe the area the player is in is a jetpack rental place? Something… maybe… sorta… like that. I dunno.

- Mothball. During the mushroom bit, the player follows the person in the jetpack. Then after the crossfade there needs to be a depressing gate blocking the player’s path. The player needs to think they might follow the person in the jetpack, and get stopped abruptly.

- Taking it away. This part hasn’t been done yet, and I probably won’t do it for a while — in this section, it flashes to a scene the player will play for real later on. So I need the details of that scene to be nailed down before I do the prologue version. But broadly speaking, it might be something like this:

- The player suddenly finds themselves in the middle of a spaceship battle happening around the floating city.

- Robin (the lead playable character) rushes out of the Iris to try to rescue you.

- You run towards the Iris.

- Something bad happens and Robin is thrown clear of the ship. At this point, the camera switches from first person to over Robin’s shoulder.

- In the distance, you see the Iris get pummled.

- Fade to the charred remains of the Iris at the beginning of the story proper.

Still a lot of details to fill in here but I think I’m on the right track. Just have to start adding details in-game now and see where they take me.