I love sets of things. On some level, perhaps we all do.

When I was growing up, my family had those Time-Life book collections. 23 books talking about the history of flight. 20 books about different countries of the world. 20 volumes on astronomy. Every now and then, we would get a new book in one of these sets in the mail, and excitedly add the book to its collection. I remember scouring flea markets many weekends with my dad, trying to find the last few records in some Time-Life music collection we’d gotten used. Our set was incomplete.

This could not stand.

Sets are fun. Sometimes, it’s infuriatingly difficult to know when you’re done with something. You wonder if you’re definition of complete isn’t complete enough. You want to add one more thing. You worry that there might be something out there you need, something that you don’t know you don’t know exists. But with well-defined sets… you know what you’re missing. You know what to look for. Most importantly, you know when you’re done. And it’s just such a satisfying feeling to know that, finally, something of yours is complete. Finished. And you can move on with your life.

I have started thinking about game developments in terms of set collection.

* * *

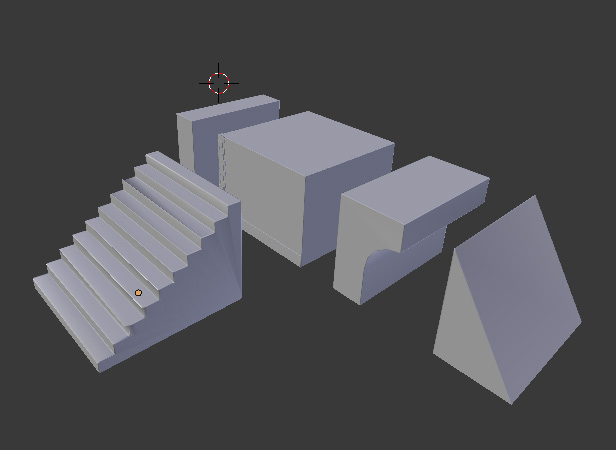

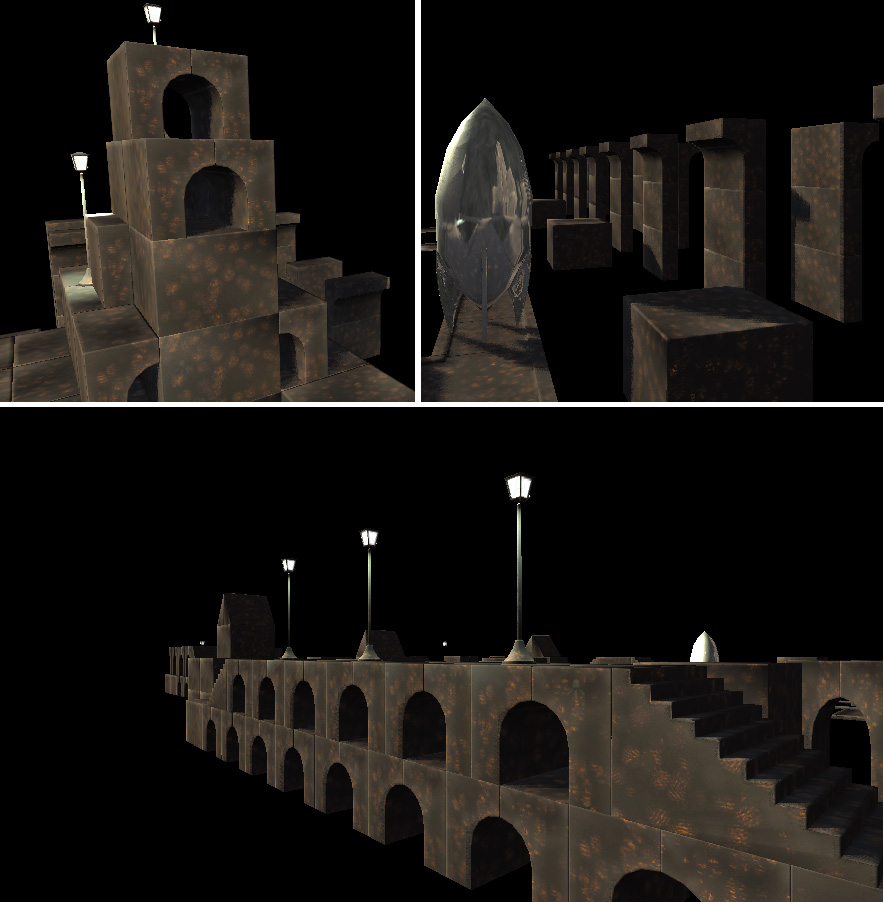

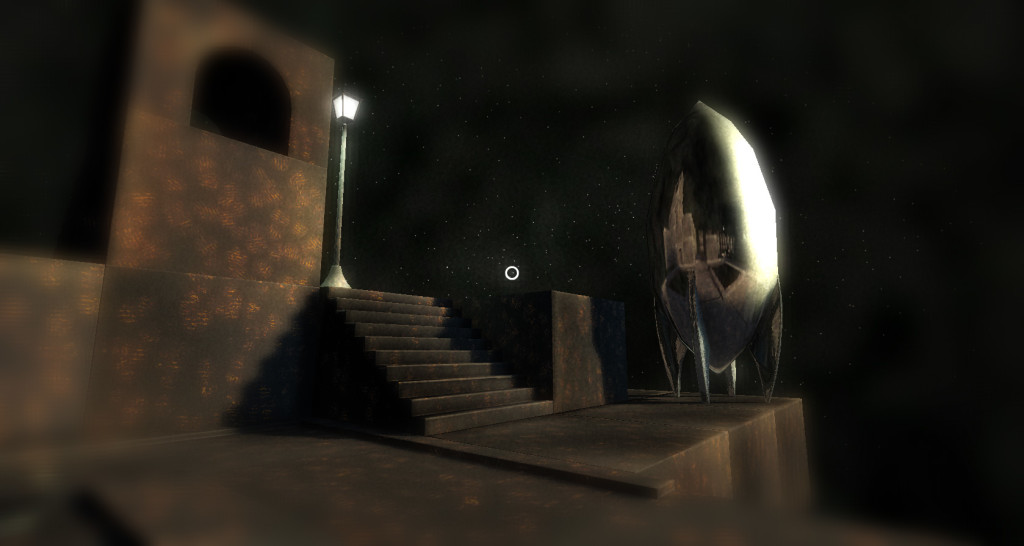

My still-in-development Global Game Jam game is all about finding new ways to traverse a world that doesn’t make walking from place to place very easy. So my first job, as I saw it, was to design a complete set of power-ups that let you move in new ways. I will know if my set is complete if you ways ways to:

Move, laterally, farther than normal, across chasms.

Jump up higher than normal.

Fall down greater distances without dying.

Move through things you couldn’t move through before.

Walk on things that were once hazardous to touch.

Skirt around and below things that were once dangerous to approach.

In very general terms — if you think in terms of what axes you can move on and where hazards are in relation to you — there are a finite number of ways one can move around one’s environment. I will know I have a workable, complete set of player upgrades if my upgrades cover all of these movement cases. And once I have those upgrades designed, I will be able to move on — because at that point, I will be done. And while I may tweak my upgrades throughout the development of this game, I will feel confident knowing that the vast majority of my conceptual work is done. I finished my set.

* * *

My wife recently alerted me to a simple approach to figuring out what scenes you need in your story:

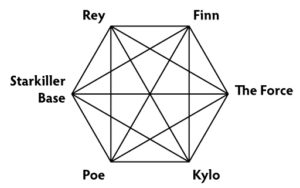

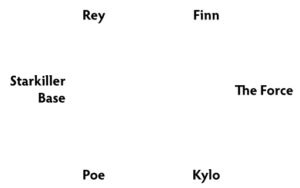

Write down every major character, setting and concept in your story, in a big circle:

Then connect all of them.

Every one of those lines is a possible scene.

Write a scene developing Rey and Kylo’s relationship.

Write something exploring what Finn thinks about this whole Force thing.

Write a scene showing how Poe and Finn meet.

Write scenes with each of the characters doing something interesting in or around Starkiller Base.

Once you have scenes for each of those lines, each of those relationships, you have a good start of a story. You have a complete set.

* * *

I am working on a board game where you wander around a fantasy world exploring fun and interesting locations. I’ve been having the hardest time figuring out what those locations should be. So I forced myself to think about it in terms of set collection.

I made a list of everything I wanted the players to be able to do in the game, in general: they should be able to find clues about the main plot somewhere. They should be able to buy and sell items somewhere. They should be able to heal up somewhere, and investigate suspicious characters somewhere.

I ended up with some 15 items: a complete set of things I wanted players to be able to do. Then I shuffled them and put them in groups of three. No matter what ended up in what group, my groups would represent a complete set. Each group would become one location. Some of them were… odd.

What kind of place would you go to heal up, sell your old gear, and get clues about the main plot?

I don’t know, but that sounds like a really interesting place.

* * *

I tend to express my design requirements in terms of feelings. I want my players to feel like they’re excitedly exploring a fantastic world. I want my players to feel nostalgia. I want my players to feel like they can fly.

This doesn’t really help me find the specifics I need to do real development work.

Expressing my requirements in terms of sets has been immensely helpful. I have a specific destination: a filled bucket. I know what I’ve done towards reaching that destination: what’s in my bucket. I know what I have left to do: the empty slots in the bucket.

The bucket is filled, or it isn’t. I’m done, or I’m not. I have real requirements with concrete, measurable criteria for completion.

And if it’s not measurable, it doesn’t exist.