I have high hopes for the game developer’s group I’ve joined. Not just in terms of getting along with the group; sure, I was worried about that, but I’m talking about, like, the group being this positive force or something. I’ve always been hesitant to look for communities of people with similar interests — I’m worried about things getting a bit insular — but I get this feeling like, I’m watching something really wonderful take shape here.

I want to do whatever I can to help this along. To that end, I’ve volunteered to give a talk to the group — maybe with some other people — about music composition.

I don’t know where or when this will take place, but it scares me a bit . Then again, this whole joining-a-developer-group thing has been all about getting out of my comfort zone from the beginning. I’m excited to continue that trend. It’s been a while since I actively looked for things I was uncomfortable with, since I looked for more opportunities to fail and learn from those failures.

* * *

Been stressing out a bit about my Robin character model — and character models in general — for Tinselfly.

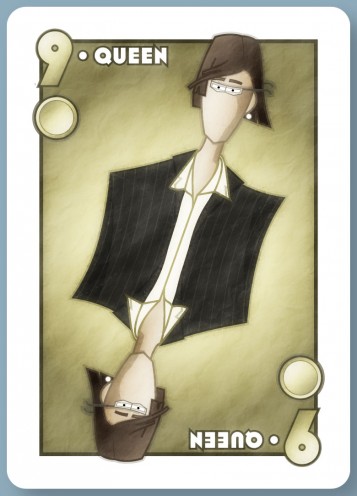

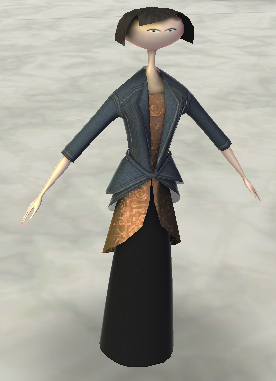

To recap, here’s what she looks like:

The odd thing about this is, in my head — if this were live action or something — I’d want the actress playing Robin to be a bit chunky. In my head, that’s how she is. She also has shoulder-length, unmanageable, curly hair, but I wasn’t sure how to model that.

But despite all that, as a stylized character in this stylized world, she’s absurdly elongated and has a simple bob.

I want the characters to look fragile. It just seemed like the right stylistic choice, the way the angular features of the characters in Samurai Jack complement the spare, action-based storytelling, or the way tile-based video game characters are frequently short and square, so the player can more easily tell what tile they’re in.

There are supposed to be elements in Tinselfly about larger-than-life people being all vulnerable, and given the 1920s aesthetic, I wanted my characters to look a little like those elongated, bronze art deco statues you see here and there.

* * *

Whatever I do, I don’t just want to make good products. I want to make good projects that feature made-up worlds that are the sort of egalitarian place I want the real world to be. That’s why Celestial Stick People has some male Lovers.

Getting some strong, layered female characters out there in the video game world is a major force driving the development of Tinselfly. I won’t argue that I don’t have an agenda here.

However, if I want that agenda to succeed, it’s imperative that I’m not preachy about it. Otherwise, the people I want to reach the most — the people who aren’t so obsessed with this whole egalitarianism thing — will simply tune me out.

* * *

So back to the skinniness.

Body image is also a hot topic in feminist discussions, and for good reason. And while I’m trying to move forward on the empowered-female-character thing, I’m kind of moving backward on the whole healthy-body-image thing.

For the most part, however, I’m comfortable with this design decision. Now, I may be completely wrong, but here’s how I’m currently rationalizing it:

- It makes sense for the story, as mentioned above. If 100% of my design decisions are based on my agenda, I’m afraid I’m getting into preaching territory. I’d still argue that there’s nothing intrinsically wrong with super-skinny stylized characters in a work of fiction; it’s when it’s ubiquitous that it becomes an issue. If my next project has super-skinny characters and thee’s no real point to it, then I’ve got a problem.

- Everyone and everything — men and women, dogs, cats, spaceships — will be just as long and skinny as Robin here. There’s not going to be a lot in the way of gender dimorphism, either, and I think that that will drive home the idea that this is a stylistic choice, not a normative statement on women in particular. (Sure, Barbie is scary looking. But compare her to the average Ken doll, and you’ll see how the dimorphism makes her so much creepier. In contrast, I like how male and female Bratz characters are similarly oddly proportioned.)

- This isn’t targeted at adolescents. I’d love to produce something fun and positive for my 10 year old sister in law; I’d love to live in a world where there were lots of products with strong, positive, non disney-princess characters that adolescents could look up to… but this just isn’t one of those products. If I were targeting that sort of age range, I’d be way more particular about what I’m including and what I’m unintentionally saying about things.

Like I said, I’m open to the idea that I’m making the wrong call here. We’ll see how this universe feels when it’s more fully fleshed out, I guess.