Well, this is very Hollywood OS.

I’ve been working on map generation for Tinselfly, and have been having some trouble with that. And last night, I wasn’t just having trouble with my code; I was having trouble figuring out how to even begin debugging my code.

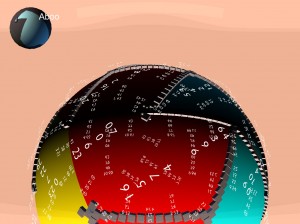

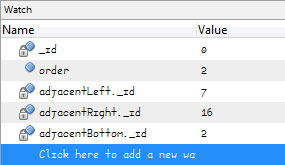

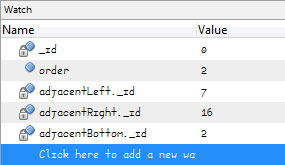

The world here is made of a bunch of triangles, and I wasn’t sure I was creating them all properly. So after an hour or two of slogging through my debugger and inspecting properties for my objects, I thought I’d just add some debugging information directly to the game world. So all the text you’re seeing, that’s information about what order my triangles were created in, what their unique IDs are, and which other triangles they’re adjacent to.

As you move around, the text moves too. Because the text is, after all, part of the game right now.

It looks like overkill, but it’s been immensely helpful.

* * *

1993. SimCity 2000 has just come out. I’m sitting in a computer lab, working on a 3d vector-graphic tank game in Turbo Pascal, a little like BattleZone.

Sure, it’s just primitive vector graphics, but it takes an insane amount of preparation to get a 16mhz computer to do this, in a programming language designed for learning, not for efficiency. Before you can draw a single graphic, you need to create a bunch of tables that the program can look at, so instead of solving complex, but common math problems every frame, it can just look up the solutions in a table.

Creating these tables takes the program a couple minutes. To make the wait a little more tolerable, I add in some messages about what the program is doing and how far it’s gotten. Some of the messages are useful. Some of them are not; they’re just silly, nerdy technobabble. Like the ‘reticulating splines…’ message in SimCity.

A not-so-nerdy friend of mine walks in and sees my program running. While he’s not as into programming as I am, he immediately picks up on the fact that this technobabble isn’t what it seems to be. He accuses me of trying to make my stuff look more involved than it really is, and walks out.

It isn’t a playful jab. He’s sincerely disappointed.

I’m mortified. Because he’s right. Sure, there really is some complicated math going on here, and getting this to work was no small feat. I want people to know that. Even the simple act of drawing a single line on the screen requires custom code that I’m proud of having implemented on my own.

But my status messages should have communicated exactly what I needed to know; no more, no less. I strip the messages out. They weren’t in my program for more than fifteen minutes.

But for years after this, I’ll be very nervous when talking to non-technical people about programming tasks. I’ll be very careful to choose words and phrases that are clear rather than impressive.

* * *

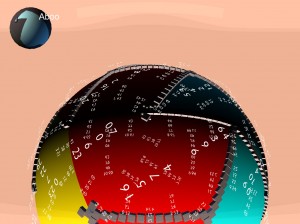

The moment I saw that globe with those numbers floating around it, I started to worry that this was more about making me feel proud about doing something complex, and less about solving a problem.

However, my problem with Tinselfly right now is all about spatial relationsips. It makes sense for my debugging information to be presented in a graphical way, rather than the text-only debugging screens I’m used to.

I kind of like silly, overproduced computer interfaces in movies. I sometimes think those computers might be fun to use.

Though in reality, overproduced interfaces just get in the way a lot of the time. You’ve got to have exactly as much interface as you need. And sometimes, just sometimes, what you need is a bunch of transparent numbers swirling around a colorful sphere. Which is kind of cool.

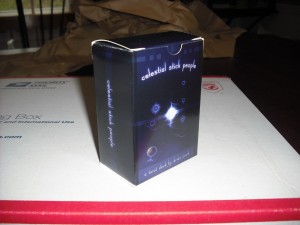

A Postal Service box. It’s big. And filled with lots and lots of paper.

A Postal Service box. It’s big. And filled with lots and lots of paper. Wrapped up in all that paper, you get a tuckbox. (It’s not shrinkwrapped, which I kind of like. Shrinkwrap is icky.) The box feels very sturdy and crisply constructed.

Wrapped up in all that paper, you get a tuckbox. (It’s not shrinkwrapped, which I kind of like. Shrinkwrap is icky.) The box feels very sturdy and crisply constructed. Sadly, I did my math wrong and this test box contains only 65 cards, not the 78 a real deck would have. So it looks a bit loose here. I just tried padding it out with regular playing cards, and everything still fits fine with 80something cards so I think we’re ok.

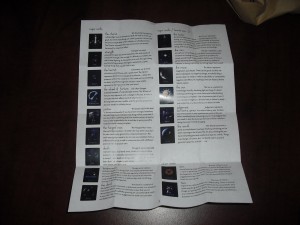

Sadly, I did my math wrong and this test box contains only 65 cards, not the 78 a real deck would have. So it looks a bit loose here. I just tried padding it out with regular playing cards, and everything still fits fine with 80something cards so I think we’re ok. The instructions come as three separate, folded pieces of paper. I’m kinda bummed about that — you have to sort the pages by hand, so I’m glad they’re numbered — but I don’t think it’s a dealbreaker. If I could squish the card reference onto two sheets of paper and have the instructions by themselves on one sheet, that might make all this feel more logical, but I’m pretty sure that’s not really doable.

The instructions come as three separate, folded pieces of paper. I’m kinda bummed about that — you have to sort the pages by hand, so I’m glad they’re numbered — but I don’t think it’s a dealbreaker. If I could squish the card reference onto two sheets of paper and have the instructions by themselves on one sheet, that might make all this feel more logical, but I’m pretty sure that’s not really doable. Unfolded, the rules are perfectly readable at least. The folds in the paper are nice and crisp; it’s not like you unfolded a crumpled up sheet here.

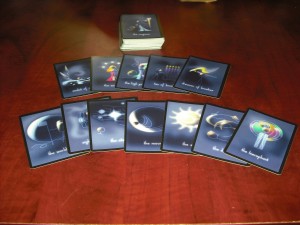

Unfolded, the rules are perfectly readable at least. The folds in the paper are nice and crisp; it’s not like you unfolded a crumpled up sheet here. And here are the cards. The registration is ok, and a couple of the 5 sets of samples I got have nice looking colors. They don’t really have that new card smell. Not exactly important, but I was surprised.

And here are the cards. The registration is ok, and a couple of the 5 sets of samples I got have nice looking colors. They don’t really have that new card smell. Not exactly important, but I was surprised.