A while ago, I downloaded this app that lets me see how much time I’m spending playing games. I seem to get about an hour or two a week in. The most I’ve spent with any one game is Star Trek Online; I’ve played it for a total of 25 hours over the last 2 years.

Those felt like pretty big numbers to me. I showed the stats to my wife, and she was appalled that I’d given a full day of my life to this one game.

I showed those numbers to some people in the local game dev group, and later on to some other friends, and they were appalled at how low those numbers were.

It’s becoming quite clear that I don’t really have a grasp of how people who are really into this stuff engage with it.

* * *

So I started playing Mass Effect. As with most big, popular video games, I wouldn’t necessarily say I like it. But the act of playing and trying to figure out what it’s trying to do, who it’s trying to appeal to… that, I find fascinating.

It seems a lot of it is about world building. I’m really, really not at all into world building normally. Whenever people start gushing about the richness of this or that built world, it actually makes me angry. I feel like it’s a waste of time, concentrating on emotionally inert minutiae that has no real value outside the context of a narrative.

But if I’m playing this game to figure out the mindset of its target audience, a big part of that is figuring out the appeal of world building, really figuring it out without being dismissive of it.

* * *

So what is this whole world building thing about, anyway? Here are some guesses:

- Historical context. Can add more layers of meaning to dialogue and events.

- Suggesting unwritten scenes. I’m a big fan of this in general. Suggesting an unwritten scene can be used to gloss over something that would be boring if you actually saw it; it can create comedic how-did-they-get-here moments, or efficiently hint at where a relationship has been going. I can see something here where the more world you’ve got, the more you can suggest using the costume, iconography, etc of your world.

- Sandbox. Fantasy/sci-fi worlds frequently exist just so the author can explore a what-if sort of scenario, and I suppose a good, robust world will also invite the audience to pose what-ifs of their own. At its worst, this can descend into self-indulgent wallowing in one’s favorite bits of a fantasy world, but I’ll admit there is real value in encouraging people to explore these kinds of things.

- Suspension of disbelief. Some people will just get annoyed if you present them with an artificial feeling world. I don’t want to pander to those people just to get them to buy my stuff… but to look at it another way: while I’m not going to be taken out of a mass-market period movie because the costuming is inaccurate, many people will, and saying that it’s ok to be lazy about costume research because the masses as a whole aren’t that picky is making your work more insular, not less.

* * *

It has always been my intention to make Tinselfly appealing to people who didn’t normally play games, or only played casual stuff. But it occurred to me the other day that the last thing I want to do is be too opinionated about what sort of audience I want to reach.

It’s about depth. Being appealing to a casual audience shouldn’t be about finding that lowest-common-denominator, simplistic presentation of Stuff That Common People Like.

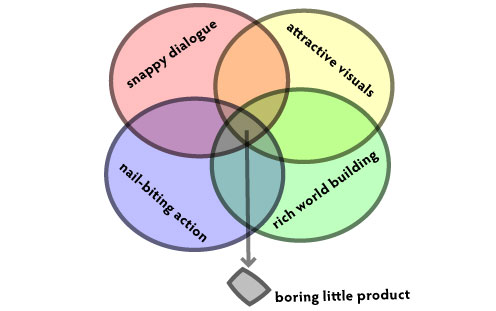

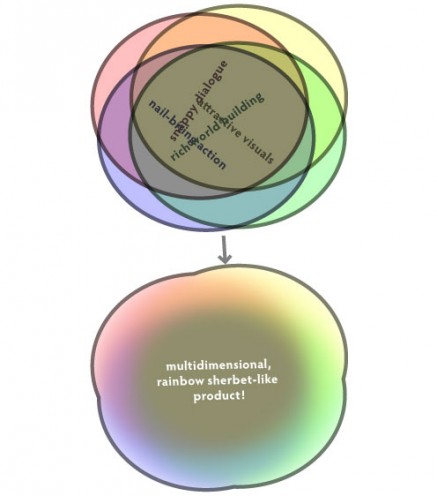

I think it should be more about the union, rather than the intersection, of appealing things. It’s about having most everything that’s appealing about your product in most every scene, but also letting those things stand on their own and shine once in a while.

So if you’ve got one person who’s just into the visuals (say, me 😉 ) and one person who’s just into the snappy dialogue (totally not me), you’ve got a good chance of getting both of those people. But that’s not the important part. The important thing is that any audience member has a variety of things to latch onto at any given moment, and can experience the work on multiple levels simultaneously, if they so desire.

* * *

This new, vignette-filled structure I’ve hit upon for Tinselfly opens up some opportunities for world-building. I was gonna pepper my main plot with these little, tangential, fairy-tale style stories set in little fairy-tale style universes, but I could just as easily package these up as little bits of history, set a hundred or a thousand years before the story proper.

If there’s an organic opportunity to give world-building fans something to play with, I should probably do it. I would do well to go ahead and put real effort into those dimensions of my product that I’m not the biggest fan of, like the dialogue and the world building; as long as it doesn’t interfere with the visuals and the story structure that I want, it can only make this better.