GDEX is coming up! It’s a game developer’s conference right here in Ohio, which I’ve been looking forward to since, well, the last GDEX I was at, back when it was called the Ohio Game Dev Expo.

I’d been meaning to get a new, knock-your-socks off Tinselfly demo ready, and… I won’t have a new Tinselfly demo for GDEX.

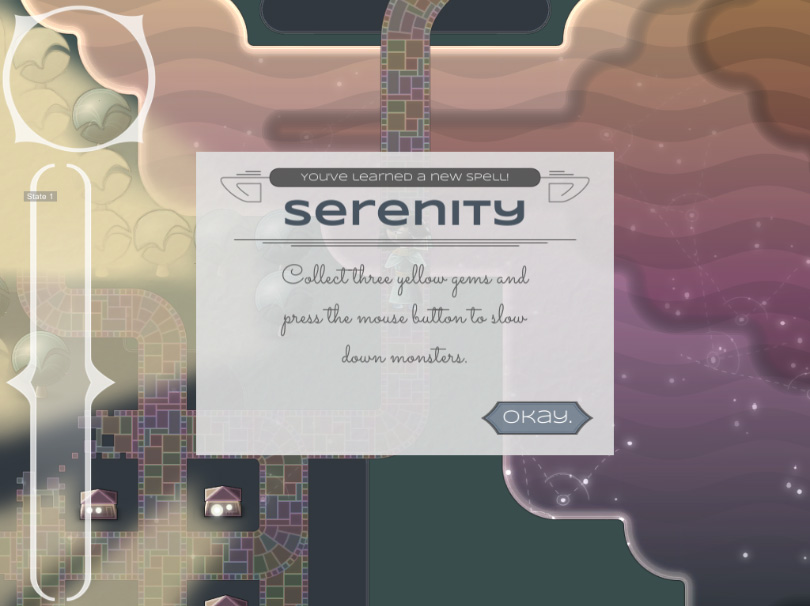

Instead, I’ve started working on Gemslinger again. It’s a nice, small project I can tinker with while also keeping room in my life for random board game contests and spending time with my family.

* * *

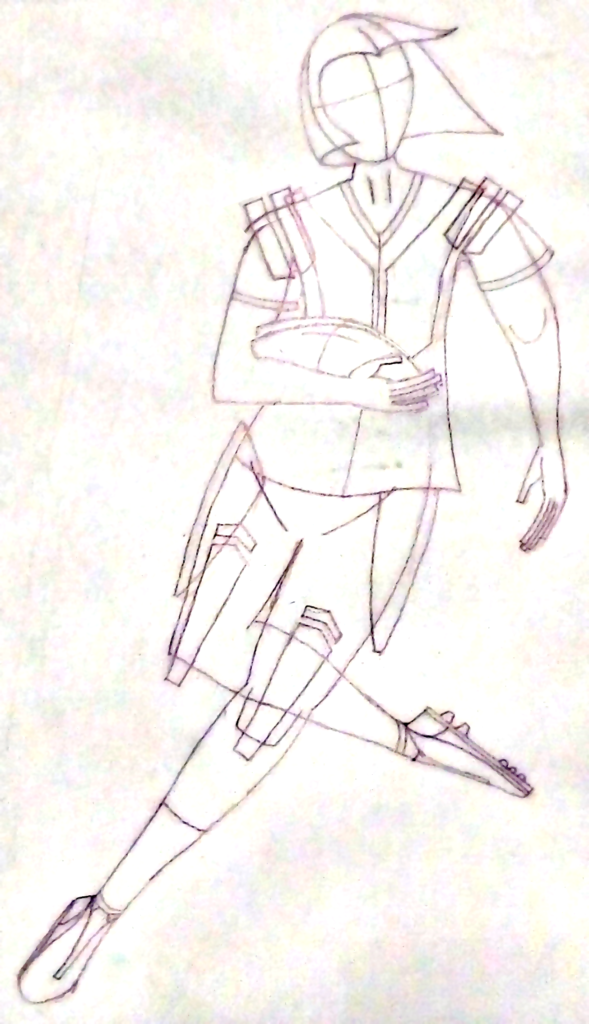

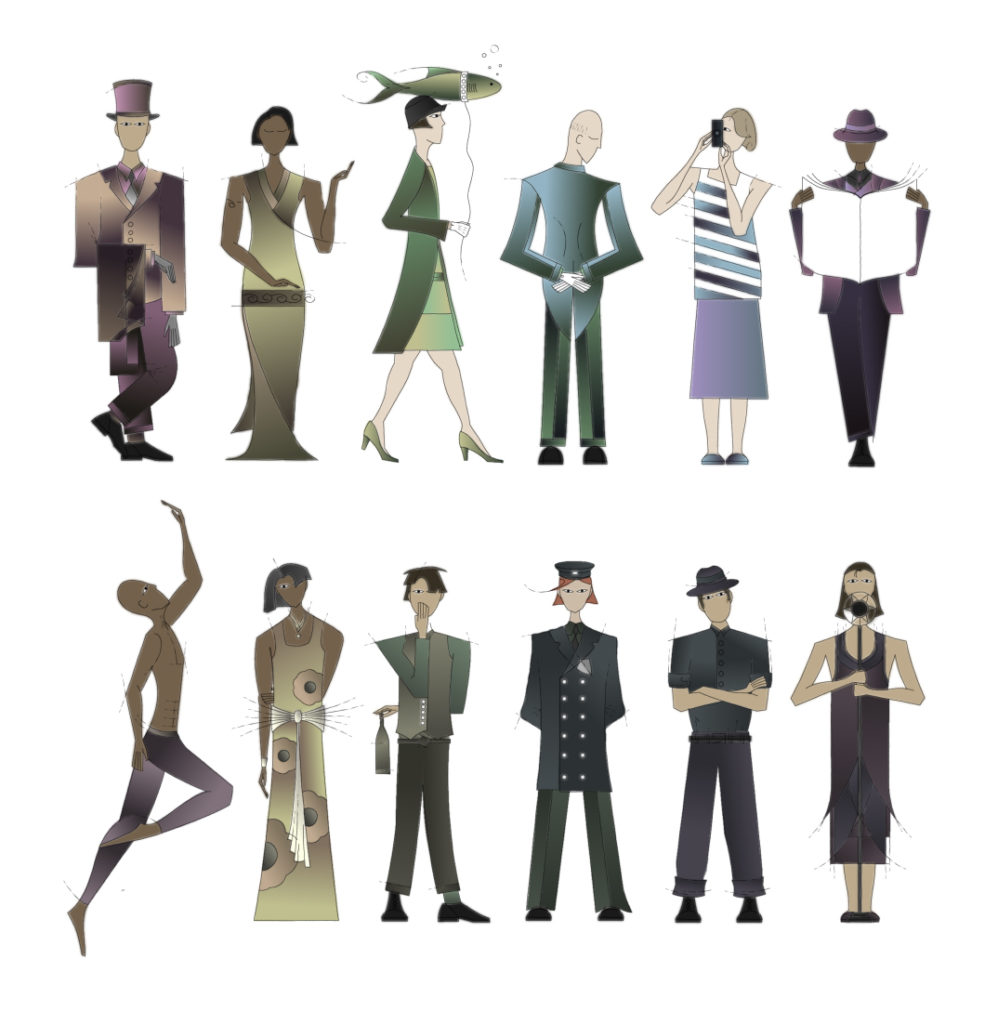

I drew a football player character the other day for that contest. I’m trying to improve my people-drawing skills, and this is where I’m at right now:

Part of this endeavor is learning how to do a good sketch before diving into tracing and coloring and whatnot.

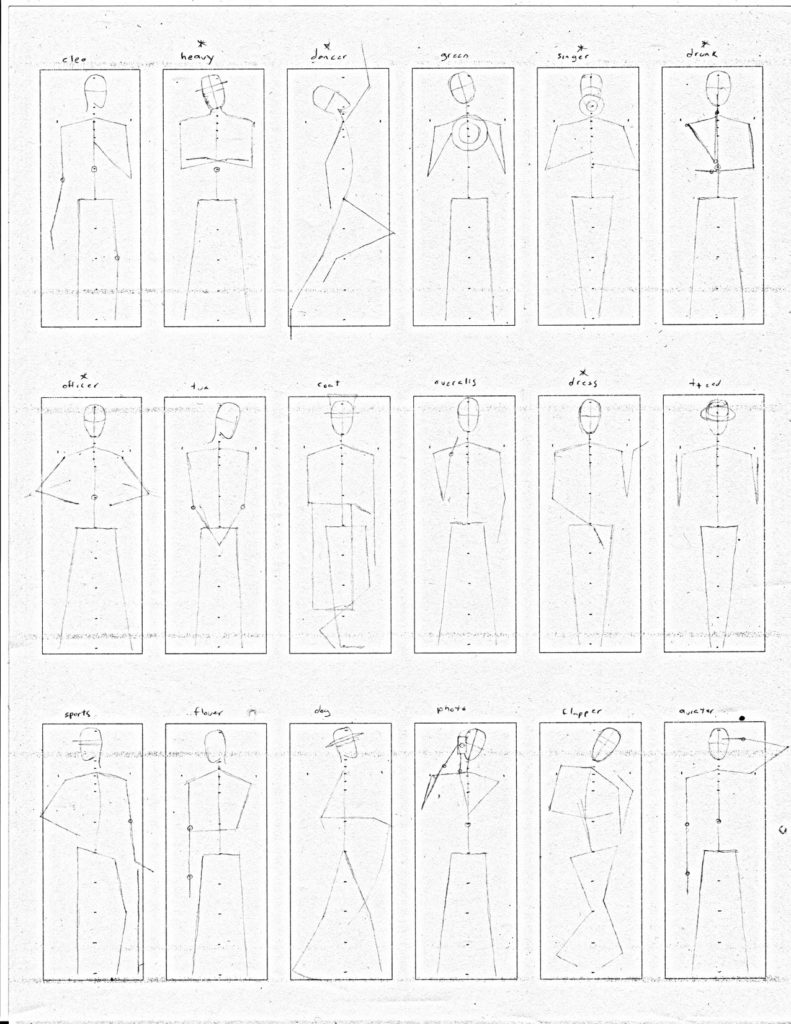

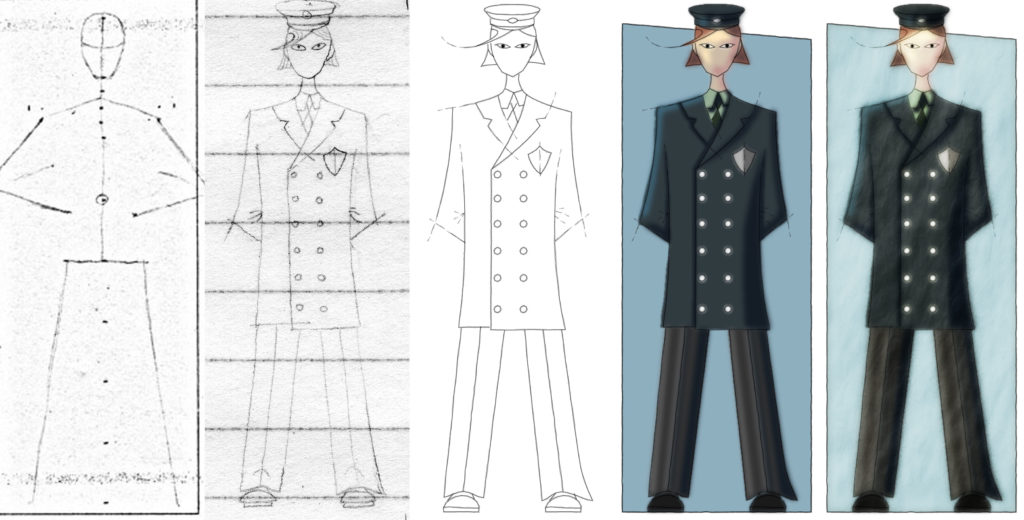

See, the last time I tried to do character art, I had little stick figure sketches, like this:

I was proud of me. The skeletons all had different poses. As far as I could tell, I was ready to start layering bodies on these skeletons.

And then, I realized, my skeletons were too skinny. Sure, they looked fine on their own — they looked how stick figures should look, basically — but once I added my character outlines things started to look strange. My characters were all unrealistically thin, there was little space between the lines of the skeleton for the character’s bodies.

Generally speaking, I need to learn more about how to make a good skeleton, and more importantly, know a good or bad skeleton when I see it.

* * *

The reason I entered that board game contest is, I have no idea how to design a board game.

Sure, I can come up with mechanics and test them and make character art, but these are just… activities related to board game design. There’s no formal process here.

I started off by trying to streamline one of my favorite board games, Arkham Horror. Which seems like a decent place to start, but it feels a little like trying to learn to draw people without ever studying anatomy. Studying the surface shapes of faces and arms and legs and drawing those surfaces is nice, but starting with a skeleton and thinking about the layers of muscle and skin on top of the bones is way better.

My board game has no skeleton, and I don’t know what a board game skeleton–or video game skeleton, for that matter–looks like.

* * *

So.

Gemslinger.

When it comes to the story and tone of this project, I think of it in terms of this one fantasy book.

In this book, an ordinary, modern-day teenager gets sucked into a fantasy world. Told in first person, she discovers the first few pages of a magic tome left behind by an old sorcerer, and she learns to cast spells herself. She wanders this world, learning about its inhabitants and the old sorcerer and seeing all the world’s wonders, collecting more pages of the tome and growing in power… until finally she can cast a spell that takes her back home. And when she gets home, no time has passed and she can’t cast anything… but she’s, you know, learned a lot about herself while on this adventure.

Pretty typical fantasy-based travelogue+coming-of-age stuff.

There are lots of illustrations in this book, but they’re not pictures of the unfolding story. They’re more like drawings the main character drew herself, as if you’re reading her journal, interspersed with notes and fold-out maps and sketches with vellum overlays. And of course, it has reproductions of the pages of the magic book the heroine is collecting.

The book is kind of an artifact of its imagined world; a pretend-non-fiction reference book like The Starfleet Technical Manual, Arthur Spiderwick’s Field Guide to the Fantastical World Around You, After Man or Dragonology. The production values are amazing, the story is a fun, easy read, and every time you look at the maps and creature sketches you notice a new detail.

It feels like more than just paper and words. It’s a book, but it hints that there’s a world hiding within it, if only you can find it. It feels like magic.

I love this book.

Trouble is, this book doesn’t exist. I’ve been looking for things like this book and they don’t exist.

It’s an imagined combination of fantasy narratives I read as a kid, narrative-less fantasy reference like the Starfleet Technical Manual-type books I mentioned above, and the Ultima V game manuals, cloth map and plastic Codex of Ultimate Wisdom thrown in for good measure.

But… this is my skeleton.

I like this skeleton.

The details of this imagined book are pretty specific. The main character’s arc, the way the old sorcerer’s story is a counterpoint to the story proper, the way collecting pages drives the narrative, the way pages in the book can surprise you with fold-out maps and envelopes containing hidden surprises.

Imagining this game as an adaptation of a book is expressing something novel in very old terms, very concrete terms, terms I can easily imagine. I can imagine holding this book in my hand. I can imaging flipping through the pages and I know how the illustrations look. I know exactly what the experience of reading this book is like.

And I know what the video game adaptation of this book should look and feel like, and how it should deviate from the book.

I want it to feel a little magical.

* * *

But, you may be asking, as I’m asking myself, how is this a better skeleton than starting off a board game design with another board game?

My source material for the board game is still very specific. I’m still thinking in terms of adapting something old and concrete, and adapting it in a novel way.

So what’s different? Why am I uncomfortable with the board game skeleton?

I think it’s about being able to see or edit the skeleton if I don’t like it.

My imagined fantasy book is malleable. It didn’t always have an old sorcerer character. It didn’t always involve collecting pages of a spell book; at first it was just pure exploration.

This imagined Gemslinger book is constantly changing, based on the direction Gemslinger the game is heading. I can re-work my imagined book and shape it and it is soft: I can mold it and remove parts and add parts to it, and as I do, I feel its hard skeleton underneath its pliable skin. I can’t quite describe it verbally and I can’t quite think about it consciously way, but I can feel it. I know it’s there.

Arkham Horror will never change based on what I’m doing with my board game contest entry. It’s static. It’s hard. When I touch it, I can’t feel what’s underneath it; I only feel its surface.

I can’t feel its bones.